Grotesque

Download PDF« The grotesque is a kind of free and humorous picture produced by the ancients for the decoration of vacant spaces in some position where only things placed high up are suitable. For this purpose they fashioned monsters deformed by a freak of nature or by the whim and fancy of the workers, who in these grotesque pictures make things outside of any rule, attaching the finest thread to a weight that it cannot support, to a horse legs of leaves, to a man the legs of a crane, and similar follies and nonsense without end. He whose imagination ran the most oddly, was held to be the most able”.

Giorgio VASARI, “About painting”, circa 1550

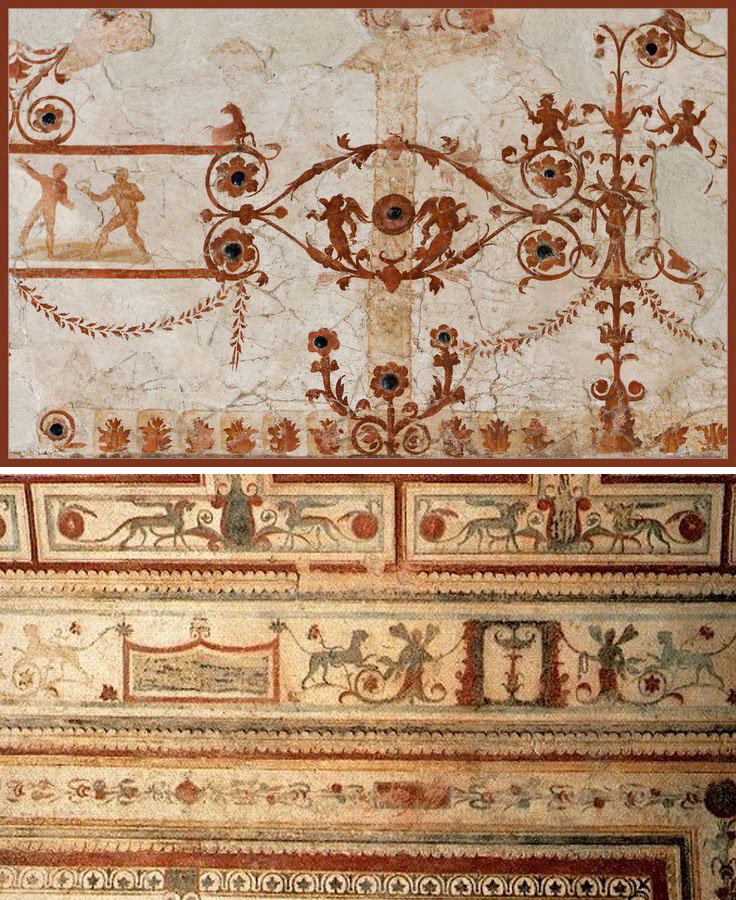

The origin and etymology of the grotesques is linked to the discovery in Rome and its countryside of roman houses and their painted decors, which were buried for centuries. Especially the ruins of the extravagant antique palace of Nero, the Domus Aurea, aroused enthusiasm: it was built for the emperor just after the big fire of Rome, and is composed of several buildings, large gardens, and an artificial lake. One after the other, artists explored those surprising rooms. Its frescos corresponded to the 4th Pompeian style: a style characterized by a linear and vegetated architecture and an ornamentation constituted of plants, animals or even monsters like the griffon or the centaur. The discovered frescos inspired a new style of decoration full of fantasy that was called “grottesques”, in reference to the “cave” (“grotte” in Italian) in which they were. While at the 15th century the taste for Antiquity was growing, Italy became the initial situation of this “renaissance” (“rebirth”) with the exploration of antique ruins and the rediscovery of their ornamentations.

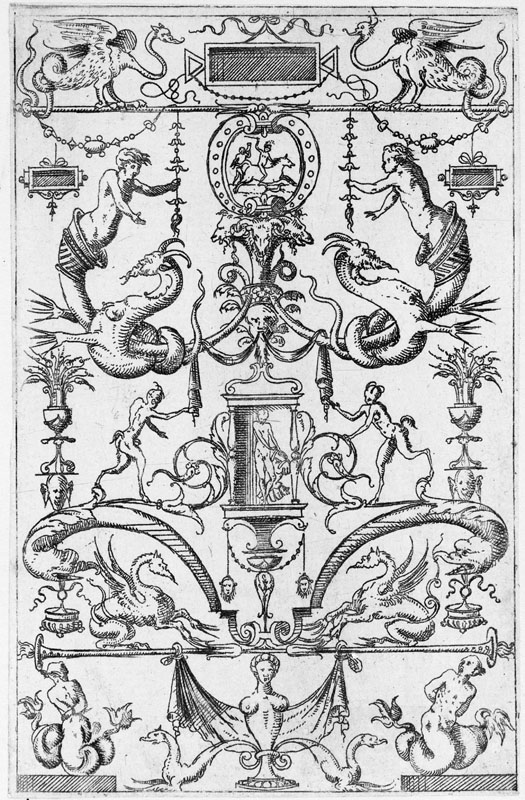

During the 15th century, the word “grottesque” lost a “t”: the spelling evolved at the same time that the style of the “grotesques” was transformed. Being able to incorporate all the imaginative forms of ornamentation was the strength of the grotesque. The word acquired a comic, ridiculous meaning. Some peculiarities, monsters, inhabited half-palmette tendrils, or even antics or chinoiseries abounded in those ornaments. Two fundamental aspects always allow to identify them: the negation of space - it consists of a weightless world where all the elements seem to float -, and the presence of hybrid forms - half-human, half-beast or half-vegetal - sprang from pure fantasy. The grotesque art is used to decorate ceilings and walls on which large paintings could not be placed and numerous painters specialized into this art, like Domenico Ghirlandaio, Raphael and Michel-Ange. Around 1518, Raphael and his workshop decorated the famous Loggias of the Vatican, and consecrated the grotesques which encountered from then an extraordinary success.

The etching and the engraving participated to the fast dissemination of the copied or reinvented grotesques patterns, and were used to report the motifs on mural paintings, tapestries, on gold or silver works or even ceramics. In France, Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, protected by the king Francis Ist, simplified the shapes of the grotesque art by creating a more harmonious structure (picture 4), which will pervade the decoration of his time. At the next century, in keeping with the French Classicism, the grotesque patterns were ruled by symmetry and harmony. After the glorious 16th century, the 18th century, with the discovery of Herculanum and Pompeii, gave a new impetus to this ornamentation. At the 19th century, the grotesques were much rarer.