Louis XVI style

Download PDFInitiated by the Transition style, the return towards Antiquity was deepened and definitive with the Louis XVI style. The proportions and volumes were equilibrated, the elegance was sober and refined: after having abused of the curved lines and the asymmetry with the Rococo, the straight lines and the simplicity of forms came back. Thus, the Little Trianon, offered by the King to the queen Marie-Antoinette in 1774, designed by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, is a good example of the Louis XVI style: its inspiration is coming from Greek antiquity, its lines are straight, but nonetheless a certain idea of lightness stands out from the building.

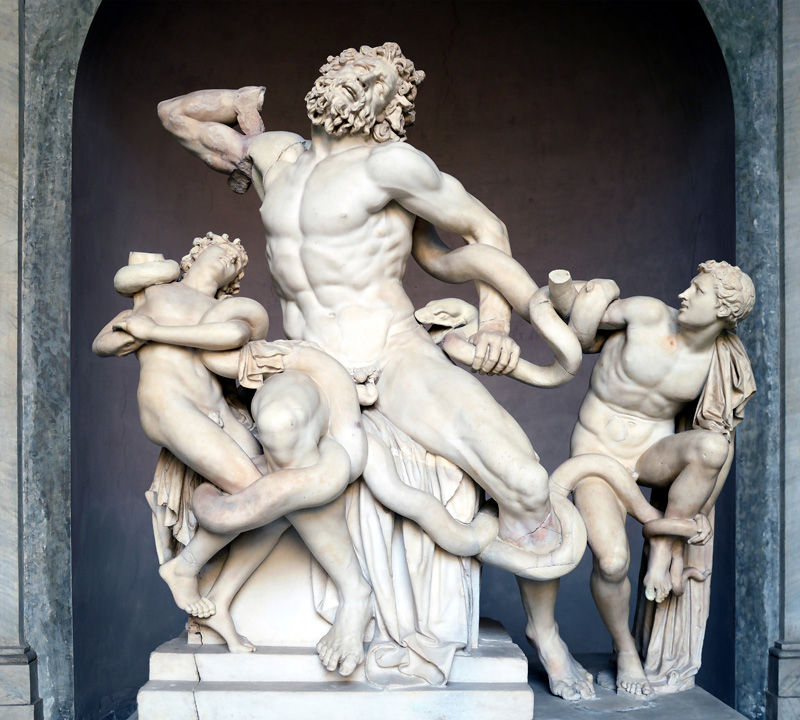

This return towards Antiquity coincided with the discovery of the ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum: a true craze sparked, around 1750, for the Greco-Roman architecture and decorations. A large number of books dedicated to Antiquity were published, artists traveled to Naples to study excavated objects and to draw frescos ; the Pantheon, ruins, or even antique statues preserved by the pope - like the Apollo of the Belvedere or the Laocoon - became known thanks to albums. The archeologist Winckelmann, an unconditional defender of Greek art, that he defined as “noble simplicity and calm greatness” went on to inspire generations of artists, architects or theorists of art, like Jacques-Louis David, Benjamin West, Lessing, Goeth and Schiller.

In the simplicity and the “pastoral” representations of the Louis XVI style, one can find its inclination for nature. At the time where the first cottages were built, Rousseau writes La Nouvelle Heloïse (“the New Heloise”), and Bernardin Paul et Virginie (“Paul and Virginia”), two novels of sentimental literature that became sources of inspiration for decorative arts. The country-style aspect of the time is well illustrated by the Queen’s hamlet at the Palace of Versailles, a miniature and bucolic village, that the king offered to Marie-Antoinette in 1782.

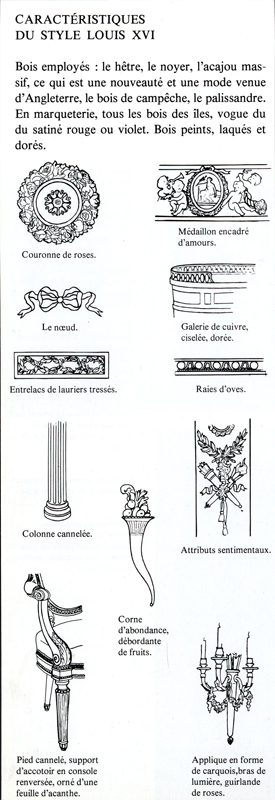

Thus, antique motifs and the liking for nature came together into architecture, interior decoration and furniture: rustic and sentimental symbols were combined with the rigorous Antiquity, under the influence of the philosophers Rousseau and Diderot. Many ornaments were borrowed from flora, and this love for nature appeared into decoration by the presence of a wreath of roses, baskets, palmettes, bows and ribbons inspired by the “taste for Nature”, sheaves of wheat mixed with meadow flowers, or even some gardening tools, hats of shepherdesses, or sickles. These motifs were mingled with the antique repertoire in which one can find trophies, greek friezes, friezes of pearl of hearts and hearts, stylized acanthus leaves. Their success depended on the sensibility of the artist who needed to adapt an idea of Antiquity, which would be source of all perfections, to buildings or furniture units of a complete different context.

Mahogany was the wood used on the Louis XVI style, in wood or veneer, appreciated highly for its solid colour due to its fine grain and for the variations of veins, admirably enhanced by the works of Georges Jacob. Mapple, amaranth and yew woods were the other types of wood that were currently used. Jean Delafosse, Riesener, Weisweler, Carlin, Leleu, Saunier and Benneman were some of the talented designers and cabinetmakers who defended this style. Ordinary furniture was polished, and beautiful furniture were inlaid or veneer. From the collaboration between Gauthière and Riesener, sprang the harmonious balance between wood and bronzes which would be at the center of the decoration of the time. Garish colors were rejected from fabrics, and the embroidery was replaced by lampas with cold reflections. The brightness of the metal gildings was attenuated by matt gildings, and the plates of Sèvres or the Wedgwood, rectangular or oval, adorned the secretaries or chiffonniers.

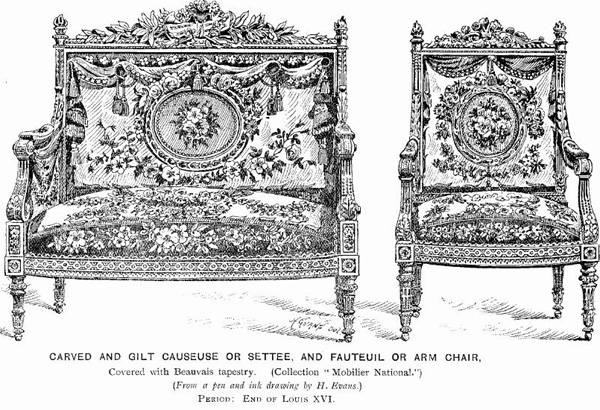

The seats were numerous, often less comfortable than under Louis XV, but finer and more harmonious. Like often in the furniture of this period, its legs had the shape of a column, fluted or in spiral, that is thinner at the base. The back was rectangular or oval, and sometimes they were partially opened to figure a lyre, a balloon or even a basket. The cylinder desk, from which the top rolls into the piece of furniture when the desk is opened, were in vogue. The cabinetmaker Riesener, undisputed master of Louis XVI’s furniture, made several ones for the king. The window displays appeared at that time when art began to be available to more people. The use of gilt bronze was massive, and today this production is one of the most rated of the 18th century. The pendulums, adorned with allegorical characters and with shapes often taken from architecture- obelisks or even triumphal arch- flourished extremely fast and decorated the fireplaces. The taste for the wallpapers appeared, and the Queen diffused them to the Court to brighten the insides, under the aegis of the important Reveillon manufactory, which was situated in Paris, near the Bastille .

The Queen Marie-Antoinette, because of her various commissions, and the “marchands-merciers” (which are a French type of entrepreneur) played an important part into the development and diffusion of this style. The marchands-merciers, who were at the same time antique dealers and interior decorators, established the link between the rich commissioners and the artists: it was in their elegant shops of the Louvre or of the street Saint-Honoré that the high people of this world went to receive some pieces of advice and renew their furniture. The most recent acquisitions of the Queen or of the Count of Condé, were exposed there before being brought to Versailles, quickly, the fashionable people would buy something that would look alike. Creating and breaking fashions, it is also all the style of this period that they impacted.