Orientalism

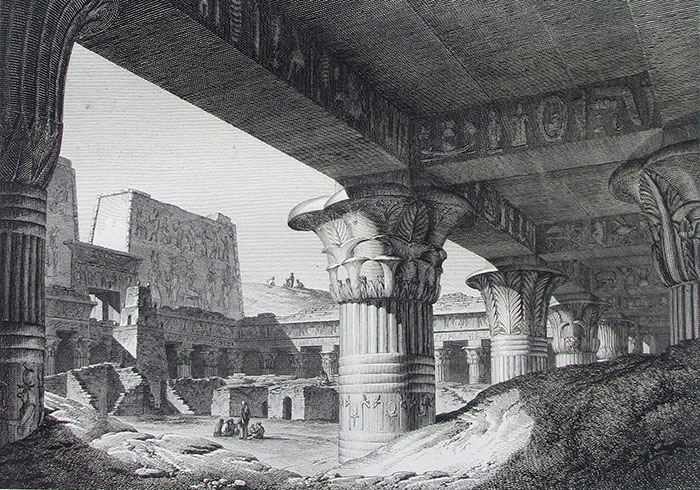

Download PDFThe Westerners interest for Orient, known as Orientalism, have its roots during the 17th century, but is on the increase during the 19th century thanks to the transport development among other things. Orientalism soon inspires all forms of art and attracts artists belonging to very different currents as it answers to several aspirations. If the movement knows a big fortune in Art, it is primarily related to political events. Napoleonic conquests, first, give the new vision of an Orient as source of a certain knowledge. Artists, like Vivan Denon, accompany expeditions and bring back studies and notebooks with new motifs. A wave of Egyptomania arises from these conquests and imprints the Empire style.

At the same time, the decline of the Ottoman Empire is at the heart of the European news and the Greek War of Independence stirs up from 1821 an important philhellene movement, especially in France, which agitates public opinion outraged by the fate of the insurgents, and contributes both to the political debate and to an unprecedented artistic craze for the Orient. The motif of the Ottoman soldier thus becomes a recurring motif in painting. The young generation of Romantics is involved in the debate with Victor Hugo and Lord Byron and the taste for foreign lands becomes a possible answer to their wealth and diversity quest.

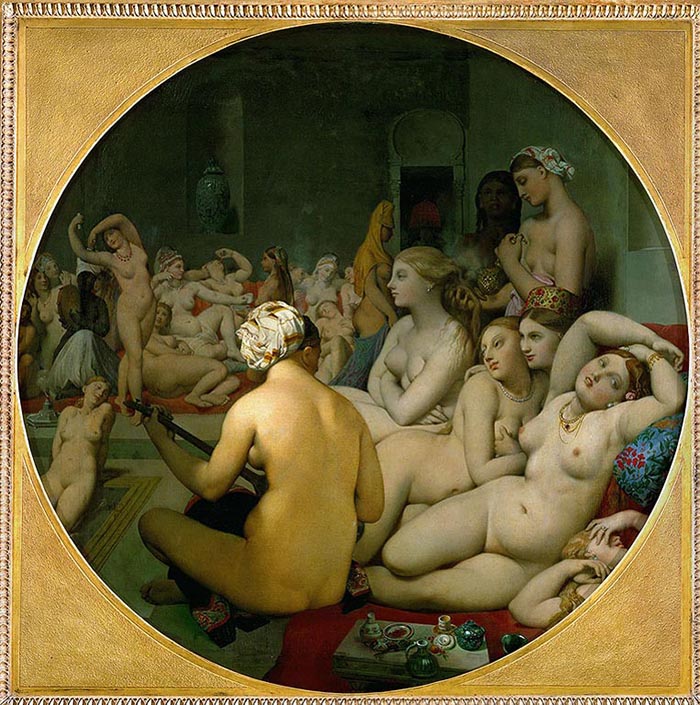

Orientalism, which corresponds to the romantic taste for foreign lands, has given rise to oriental completely fantasized representations and especially as Orientalism has vague geographical and historical boundaries. Realism and ideal are mixed in this new pictorial wave: Orientalism, in other words the Western vision of the East, is born. Algeria for example becomes a source of inspiration with the colonial expansion (Charles X decides in 1830 the French expedition). Delacroix thus paints Women of Algiers: in languid postures, the women have an idle life. Oriental women, indeed, fascinate Europeans. Associated with a provocative and nonchalant sensuality, and a certain mystery imbued with power and charm, they become one of the preferred motifs, whose Ingres is inspired by in his Turkish Bath with the multiply nudes painted according to the classic canons.

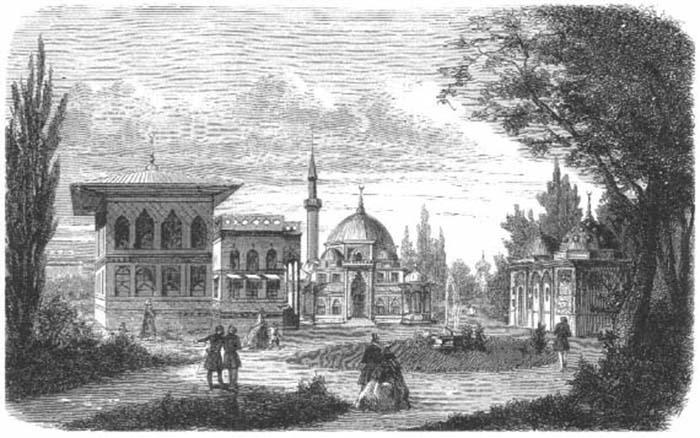

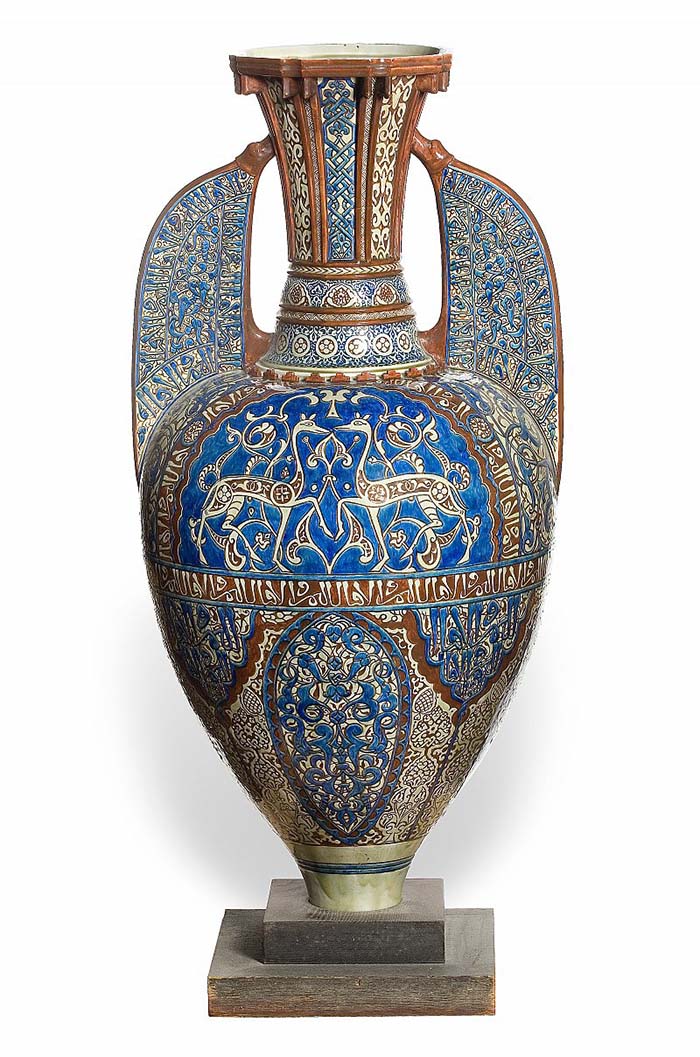

After having widely inspired painting and literature in the first half of the 19th century, Orientalism, thanks to the World’s fairs, spreads out in decorative arts and architecture which take their motifs and their techniques in the Orient. From the World’s Fair of 1867 , Europeans are both tempted and surprised by the many Eastern pavilions, like the one of the Ottoman Empire built by Léon Parvillée. Ceramists and glassmakers in particular, such as Theodore Deck and Philippe-Joseph Brocard, take their techniques and their decorations from the Arab art they want to compete. Inspired by Moorish Spain, now included among the Orientalism, Théodore Deck sepcializes into turquoise ceramics with plant motifs.

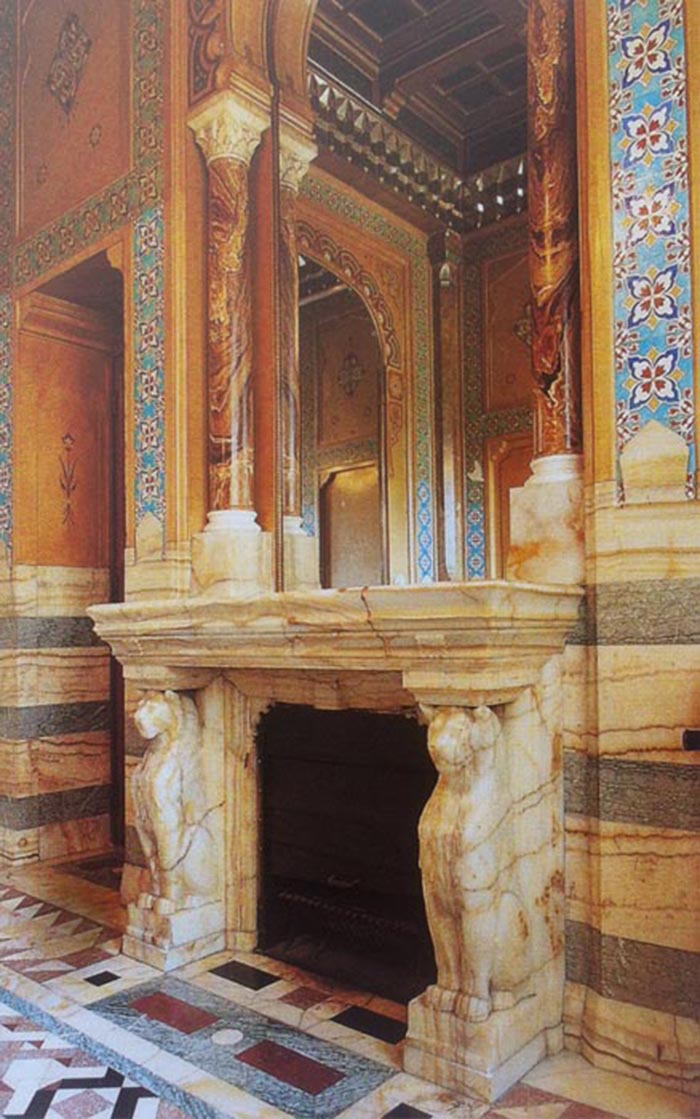

During the conquest of Algeria, onyx careers are rediscovered in 1849. From then, onyx will be one of the most coveted material in Europe. The Hôtel de la Païva in Paris, named after the socialite who had it built from 1856 to 1865 at 25, Avenue des Champs-Élysées, overflows with sumptuous onyx decorations, as the Neo-Moorish style bathroom, and especially its imposing fireplace with lion’s paws.

Charles Cordier (1827-1905) will be the author of a series of busts called "Negroes" in bronze and onyx.

Orientalist decorative arts, as in literature and in painting, are both fantasized and highly studied. Imbued with eclectic atmosphere, the decorative artists create works with an orientalist decor while trying hard to reproduce the antique techniques. Philippe J. Brocard, collector and restorer, studies directly the oriental works and thanks to him the enamelling on glass is born again.

This Bowl, exhibited at the Orsay Museum in Paris, is characterized by a great technicality with its perfect opaque and translucent enamels which rival their Egyptian and Syrian models of the 13th and 14th century. Some of these creations, perfectly inspired by the originals, are sometimes difficult to recognize. However the presence of dragons on the feet, taken from Asian art, is symptomatic of another of the greatest trends of the 19th century: eclecticism. In this same spirit, this Vase "Elephant" made by Christofle and exhibited during the Paris World's Fairs of 1878 and in 1889 presents this double inspiration: the top is Oriental inspired while the foot is Asian inspired.

More than an artistic current, Orientalism is part of the surrounding political then aesthetic climate, even a certain way of life. Barbedienne, a very famous foundry of the time, specializes in antiques copying and realizes daily works like this Ornemental plate with Persian decor or this Pair of ornamental vases designed by Constant Sévin. Moreover, some eccentrics, whose Pierre Loti was surely the most representative figure, attired themselves with oriental costumes and organized masquerade balls in honor of these exotic lands. Orientalism spread in many areas and artistic fields and will continue to inspire avant-garde artists in the early 20th century such as Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee.