Victorian Style

Download PDFThe Victorian Era was the period of Queen Victoria I of Britain’s reign (from June 1837 to January 1901). It represents a climax in the history of the country particularly in view of economical prosperity. Great Britain was very influential on the international scene : the « Queen of the Seas » was reigning supreme on the vastest empire ever known. The Victorian Era was marked by the first World’s Fair : The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations of 1851 which took place in London. It illustrates the highest point of Britain’s greatness.

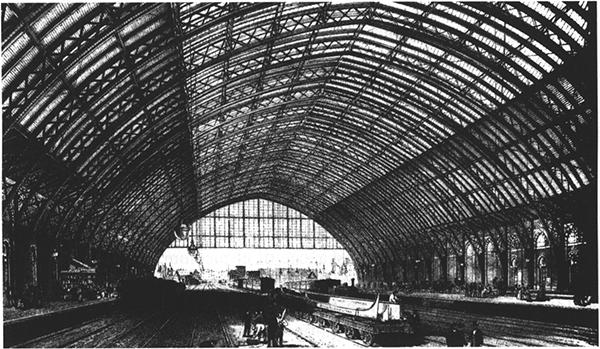

The society is upset in response to the Industrial Revolution which is in a second phase characterised by the development of the railway and the metalworking industry. Such changes led to the emergence of two antagonistic social classes : the working class and the middle class, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. The latter experienced a considerable rise and kept increasing its wealth thanks to the technical and scientific progress. The members of this emerging social class are busily involved in the artistic renewal because of their drive to compete with the aristocracy.

Social division into different groups having their own interests and identity partly explains the eclectism in terms of forms and the interest in different sources of inspiration during this period. Diversity and variety were taking precedence over uniformity.

One can compare the Victorian style to the Napoleon III style which grew in France during the period. It is indeed a composite style characterised by its richness which mixes different sources of inspiration descended from traditions of the past. The Victorian period is one of arrogance and apparent confidence that probably covered a profound insecuity. As a symbol of luxury and greatness, Victorian style was yet very affected by Romanticism which meant to stimulate the imagination, to provoke the dread, to arouse the passions and to evoke mystery. The period is nonetheless marked by a renewed interest for classical forms especially on the part of business men who wanted to legitimate their wealth and their power thanks to models from Greek and Roman Antiquity. This interest is significantly fueled by the so-called Grand Tour which began to develop during the 18th century as a result of the Herculaneum and Pompeii’s discoveries. This travel provided artists access to a Classical repertory and enabled a new breath in their works, giving them the greatness of the Antique models.

However, the 18th century’s aristocracy favoured Great Master’s works they could buy during their travels in contrast to new Victorian patrons who acquired works by contemporary British artists. The bourgeoisie favoured subjects which were more easily identifiable, narrative paintings and genre scenes, particularly during the first part of the Victorian era. This taste for Realism and narrative works has continued for decades but finally faced competition from an other artistic movement preaching a more sophisticated and poetic art which soon seduced aesthete collectors from the class of the businessmen. Indeed, the Victorian Era was marked by the Aesthetic Movement which impregnated all the artistic fiels : litterature, art or even music. This trend spread in European countries and advocated "Art for Art’s sake". Great artists such as Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Sir Frederic Leighton, Edward Burne-Jones or Albert Moore cultivated the worship of beauty. This aesthetic quest is highly visible in paintings from the period which spotlight the women as objects of desire or femmes fatales, often represented as antique or medieval heroins. As in France, the mythological nude had success, especially with the bourgeoisie. The ornemental abundance which is characteristic of Victorian interioriors and architecture influenced artists. They realised somptuous decors for a few wealthy patrons.

Victorian architecture illustrates very well the different sources of inspiration proper to the style. Indeed, some architects chose a Neoclassical style as the Royal Albert Hall of Arts and Science’s creators. It was inaugurated in 1871 in honour of the late husband of Queen Victoria. Some others were inspired by the medieval period which attracted a renewed interest from the general public. As in France, "neo" styles multiply and the Victorian artists drew on Neoclassicism, Gothic Revival , Romanesque Revival or Neo-Renaissance style.

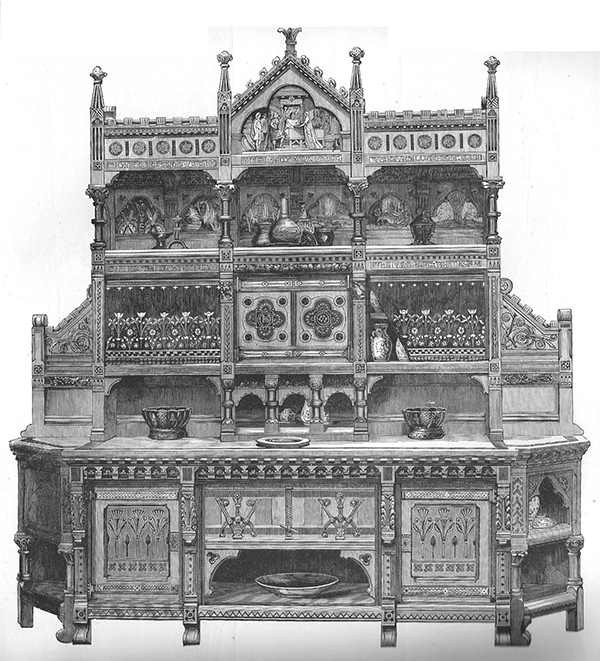

Victorian furniture, like Georgian furniture before it, stems from historical models and borrows elements from different ornemental vocabularies related to architecture or furniture. As in France with the , embellishment took a prominent place in the field of decorative arts. The Victorian style is rich and abundant, it puts emphasis on decoration and on noble materials. The term bric-a-brac from the French vocabulary appeared during this period because of the multitude of art objects which were displayed in Victorian interiors. These decors were decorated by furniture coming from previous periods. Victorian furniture keeps some elements from the Gothic Revival as dark colours, an elaborate work of sculpture and a rich adornment. The curved lines of the Victorian furniture and the whole interior decoration (wood panellings, garnitures…) are very marked by ornemental vocabulary from the Rococo and the Louis XV styles. The so-called "French Style" had indeed began to spread over Great Britain right after the French Revolution and the dispersion of the works of art. King George IV, who reigned from 1820 to 1830, were a great advocate of this trend. It led to the production of furniture, fabrics, ceramics or silverware in this French taste. As a supreme symbol of luxury and elegance, the French style was a must between 1835 and 1880. Rich colous, curves and windings, rich decoration and elaborate garnitures influenced British artists. The pieces from the Sevres Manufacture were for example copied by the Minton Ceramic Factory in Staffordshire whose pieces were displayed during the World’s Fairs.

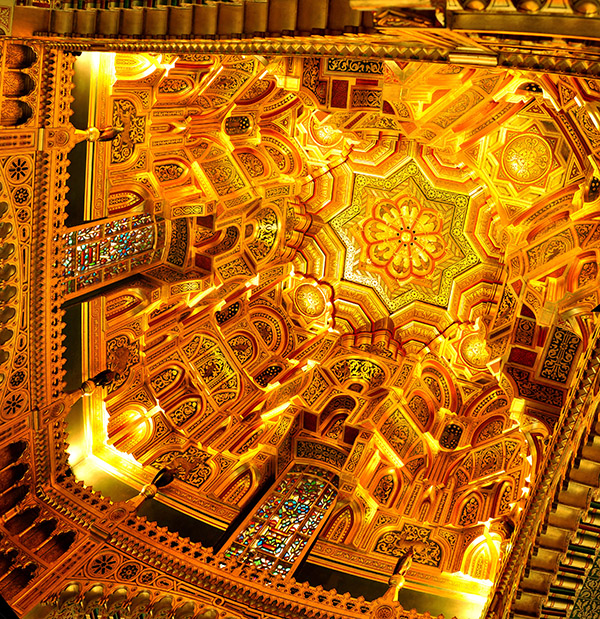

The Victorian style was also marked par a taste for the Middle and Far Eastern countries which had spread in Europe for several centuries. The architect William Burges participated in the Gothic Revival but his works illustrates also this oriental tendancy. His washstand from 1879 kept in the Victoria and Albert Museum and realised by John Walden for the guest room of Tower House, Burges’ residence in London, is a perfect illustration of Victorian syncretism. The architect doesn’t hesitate to mix Moorish and Japanese sources of inspiration. His Arab Room in Cardiff Castle evokes Pre-Raphaelite views of the harem which resonate with some French artists like Théodore Chassériau. Romanticism in the field of decorative arts contributes of the development of Exoticism. It plays a part in the medieval heritage’s revalorisation with the novels of courtly love and other chevaleresque stories. The St George Cabinet kept in the Victorian and Albert Museum illustrates all these different origins. Realised in 1861-1862 by the decorator William Morris, it stages the legend of Saint George and the Dragon which influenced French Symbolist painters and Pre-Rephaelite painters as well. He chose noble materials and particularly an exotic wood : the mahogany.

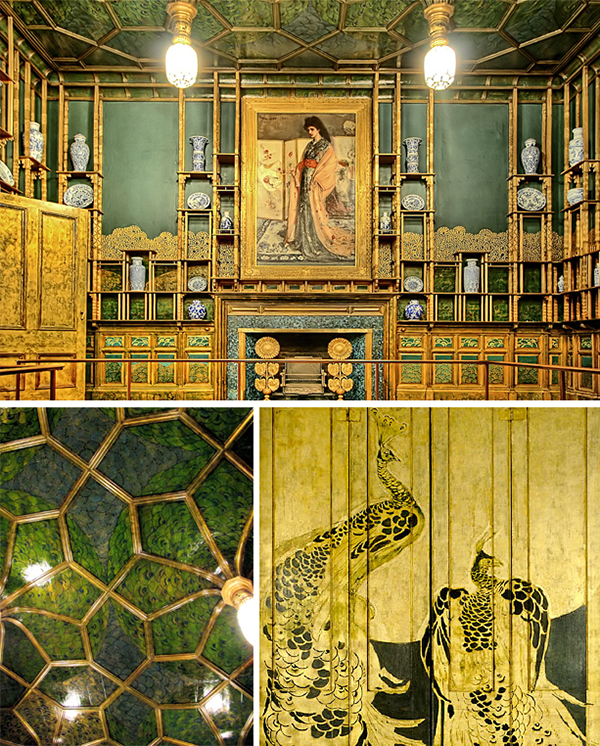

The most renowned architects and critics (Burges but also Owen Jones, James Fergusson or John Ruskin) are very interest in Middle and Far Eastern arts. The famous Peacock Room by James Abbott McNeill Whistler is a great example of the Anglo-Japanese style which developed at the time. In 1853, Japan reopened its borders and Japanese art influenced European furniture with its simplicity and its purity. Some artists adopted a vocabulary of forms inspired by nature, calligraphy or Chinese and Japanese myths. This is how some architectural elements from Chinese temples are visible in the works of some French artists like Gabriel Viardot along with some vegetal motifs or oriental dragons.

Victorian style which is composed by a multitude of stylistic elements stemed from various and rich ornemental vocabularies was marked by the development of two new styles towards the end of the 19th Century : the Arts and Crafts Movement and the Liberty and Co. Style. Arts and Crafts followed the medieval tradition by preaching the virtues of craftman’s work and employed sophisticated but yet simple forms from the 18th and 19th centuries. The Liberty and Co. Style was inpired by Japanese, Chinese, Persian, Indian or even Egyptian works of art. As in France with the Egyptomania, the time of the Pharaohs fascinated the general public. This style’s name comes from a London store founded by A.L. Liberty which displayed merchandise from Middle and Far East and whose activities extended to the fields of fashion, furniture or event art objets (vases, clocks, jewelry, tapestries…) Anglo-Oriental artifacts mixed with items from current styles then with Art Nouveau. A.L. Liberty faced constant solicitation from his clients so he had to employ architects like Arthur Silver or Archibald Knox in order to meet the increasing demand.

Bibliography :

COOPER, Jeremy, Victorian and Edwardian Furniture and Interiors : from the gothic revival to art nouveau, 1987, Londres, Thames and Hudson.

WRIGHT, S.M., The Decorative Arts in the Victorian period, 1989, Society of Antiquaries of London : distributed by Thames and Hudson.

CROOK J.M., The Rise of the Nouveaux Riches : style and status in Victorian and Edwardian architecture, 1999, London, John Murray.

DOBRASZCZYK Paul, Iron, Ornament and Architecture in Victorian Britain : Myth and Modernity, Excess and Enchantment, 2014, Burlington (Vt.) Farnham : Ashgate Publishing Company.

GERE Charlotte, Artistic Circles : Design & Decoration in the Aesthetic Movement, 2010, London, New York : V&A Publication : distributed in North America by Harry N. Abrams.