World's Fair of 1851

Download PDFIn the context of an industrial revolution, the flourishing of capitalism and free trade, the industrial exhibitions, at first national, enable to share inventions opening the future’s horizons. In 1849, the Exhibition of Manufactures and Art in Birmingham opened by King Albert gave the latter the idea of expanding this concept on an international scale, so as to be able to confront the progress of all nations.

Thus the first World’s Fair was held in London from May 1 to October 15, 1851 at the Crystal Palace. The reign of Victoria thus demonstrated its modernity and its adherence to a liberal philosophy, where international trade would be the guarantor of peace and the flourishing of human genius.

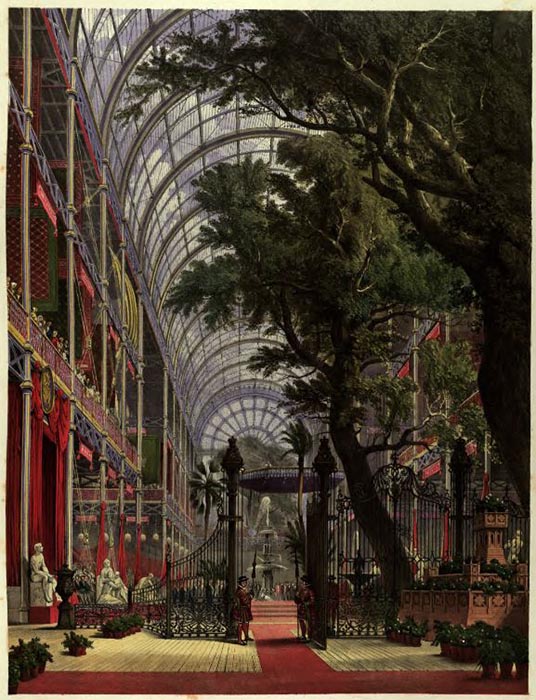

The Crystal Palace is designed for the occasion by Joseph Paxton, and built by Owen Jones. An iron and glass giant with an area of 8 hectares, built in a short time thanks to modern prefabrication methods, this building represents a tour de force demonstrating the progress of the industry. In addition, Queen Victoria puts this modern greenhouse at the service of preserving nature by preserving centuries-old trees, thus illustrating her vision of progress. The Crystal Palace was definitively destroyed by fire on November 30, 1936.

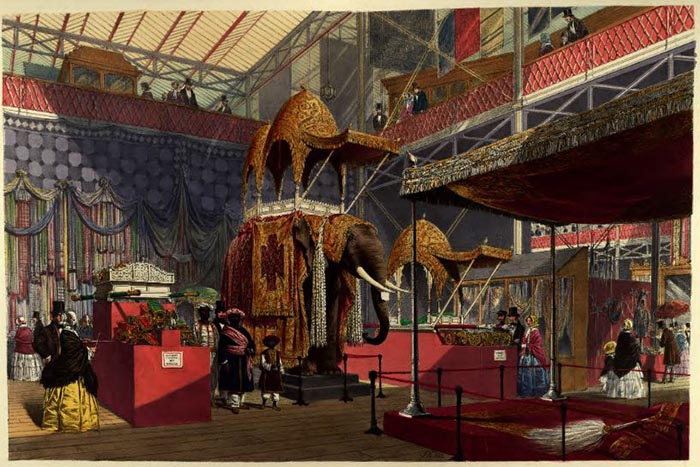

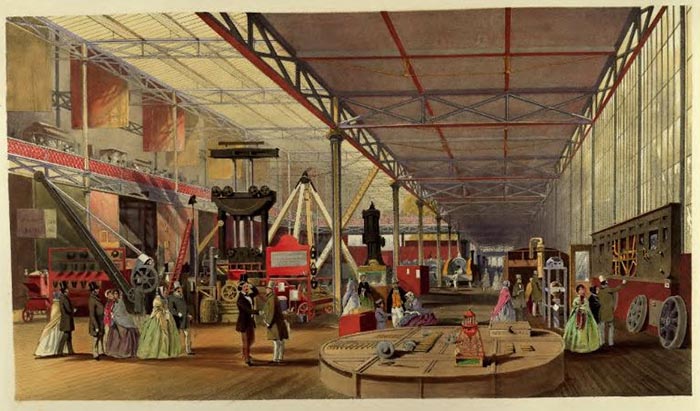

A showcase of Britain's supremacy in the world economy and in industry, the Exhibition is conceived as the presentation of the products of art and industry on a very large scale in each country. The interior is divided into four sections, which were reused for the next World’s Fairs : raw materials, machinery, manufactured products and art objects. For each, national pavilions showcase their best productions and innovations. England dedicates a large part of the building to the exhibition of its own British and colonial production, for it is then the largest Empire in the world.

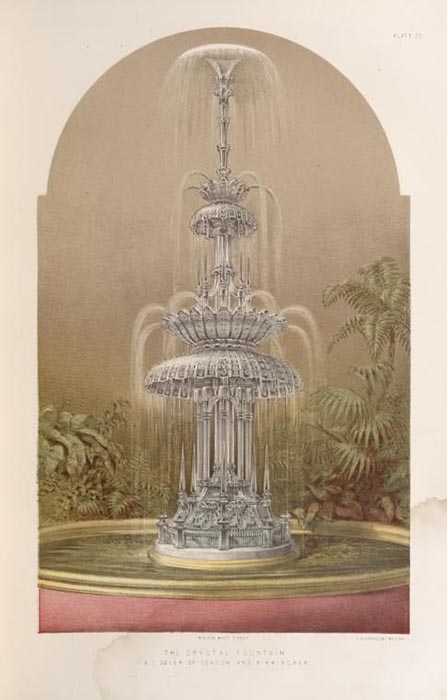

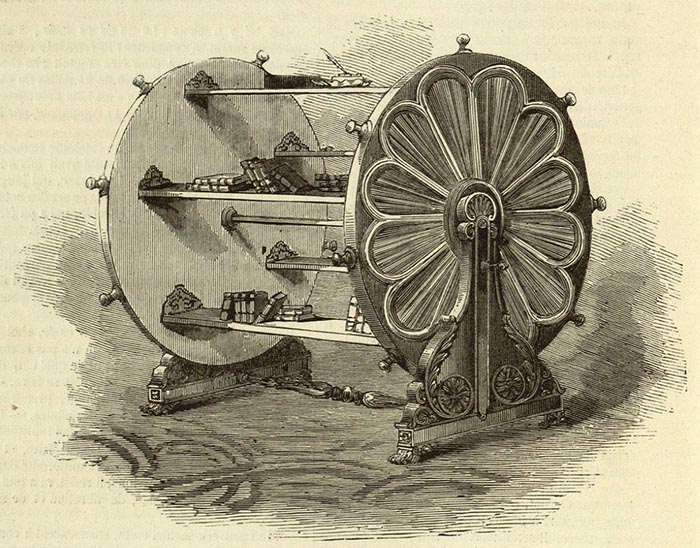

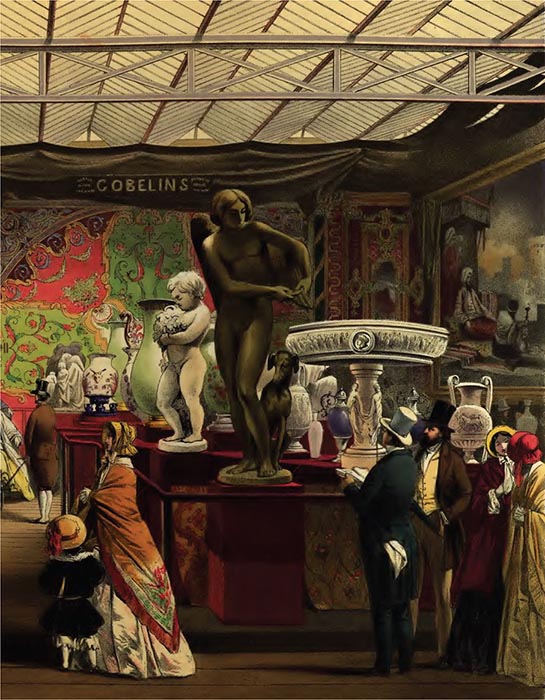

Dickinson's color illustrations are valuable testimonials of this event, and can be seen in the beauty of Osler’s monumental crystal fountain, who became one of the world's greatest crystal chandelier makers. Dickinson also immortalized the impressive pavilions of India, China, Canada, as well as the machines of the time. The curiosities of the Exhibition are abundantly relayed by the press, and some amazing inventions of the time are still preserved, such as Dr. George Merryweather's “Tempest Prognosticator”.

The section of art objects contains treasures of furnishings and decorative arts, overmantels, beds, chandeliers, goldsmith’s diner services. In the French pavilion, the toilette of the Duchesse de Parme by Froment-Meurice is highly regarded for the quality of its goldsmith's work, while the mobile and pivoting seat in the American section is praised for its ergonomics.

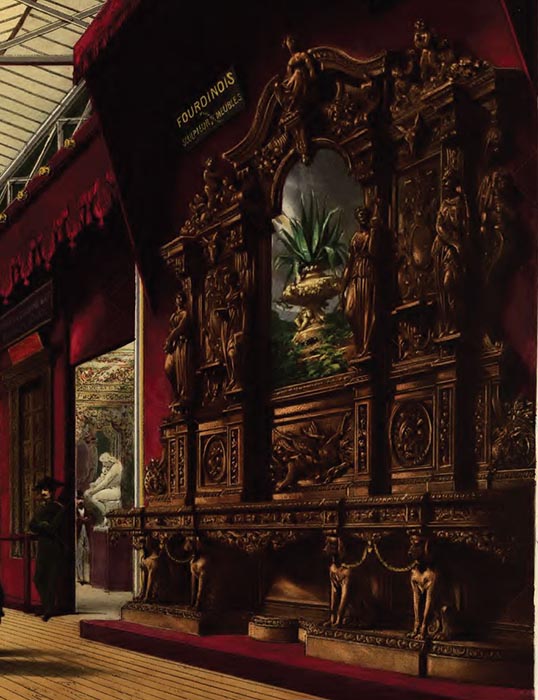

France exhibits the goldsmiths Froment-Meurice and Christofle , the bronze-manufacturer Barbedienne , the cabinetmaker Fourdinois whose furniture is judged to be of artistic value equal to sculpture. The factories of the Gobelins and Sèvres are also particularly valued.

The "Medieval Court" pavilion, also visible in Dickinson's illustrations, features medieval-style decorative objects and Gothic furniture in kit form. The strong repercussions of this pavilion, both in England and in France, decisively influenced the Neo-Gothic style.

The 1851 World’s Fair inaugurated a practice of far-reaching success, creating an artistic and technical dialogue beyond frontiers.

Bibliography

- Le livre des expositions universelles 1851-1889. Ed Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs 1983.

- Le Palais de cristal : journal illustré de l'exposition de 1851

- Dickinson’s Comprehensive Pictures of The Great Exhibition of 1851, Londres, Her Majesty’s Publishers, 1854.