Gilt bronze

Download PDFCrafting an object out of gilt bronze demands a considerable amount of work and the participation of several workers and different trades. Firstly, a sculptor creates a mock-up of the object out of terracotta or wood, following a drawing or model. Then, after printing a mold of the mock-up, the smelter-chiseler smelts the bronze by casting the molten metal into the mold. The chiseling is very important to the value of a bronze piece. At this step, the smelter-chiseler must render the model, slightly affected by the smelting, as closely as possible. This aspect of his trade is close to that of a sculptor, and only the best artisans are allowed to complete this step.

Next, there is the gilding phase, that used to be executed by the chiseler-gilder, until Louis XVI decided to combine the smelter-chiselers and the chiseler-gilders who kept fighting each other for rights. This phase can correspond to two different techniques: mercury gilding (or ground gold) and gold leaf.

For the first method, gold that has been broken down into lime or ground on a grinding stone is mixed with mercury. The bronze object is then covered with this amalgam, and heated to make the mercury evaporate and the gold stick to the bronze. After cooling, the gold is crafted with different techniques – matting, burnishing, which brings out the volumes, details, and the coloring of the gold. Mercury gilding is usually very high quality, solid and long-lasting. However, mercury vapor is known to be extremely toxic and dangerous for the workers' health.

To carry out a gold leaf gilding, one must prepare the gold in leafs or booklets that are placed on a pad and set with a brush on the metal, turned blue by the fire. This gilding is not as resistant as one created with an amalgam and less suitable for subtle details, but it is less expensive.

Gold-plating, invented in 1827, did not create toxic vapor so was a solution for preserving the artisans' good health.

Gilt bronze can be found in fireplaces, on stairway railings, door locks, luminaries (chandeliers, lanterns, and candelabras), on furnishings, in clockwork (pendulums, clocks, and barometers), on mounted vases, fireplace frames, and ink-pots. Among the most beautiful examples of gilt-bronze statuary, we must mention the Pont Alexandre III (Alexandre III Bridge) in Paris and the four gilt-bronze statues placed on top of its pillars following the theme of Renown Holding Back Pegasus. This bridge, inaugurated at the World's Fair of 1900 , was designed by the architects Joseph Cassien Bernard and Gaston Cousin. The four Renowns were sculpted by Emmanuel Frémiet, Pierre Granet, and Leopold Steiner. Another example is the equestrian statue of Joan of Arc, Place des Pyramides, made by Emmanuel Frémiet in 1874. Finally, the monumental statue of Athena (about 10 meters high) that adorns the Fountain of the Porte Dorée in Paris was made out of gilt bronze by the sculptor Léon-Ernest Drivier for the colonial exhibition of 1931. It was situated in the Porte Dorée Palace peristyle, in front of the main entrance, and was titled “France bringing peace and prosperity to the colonies.”

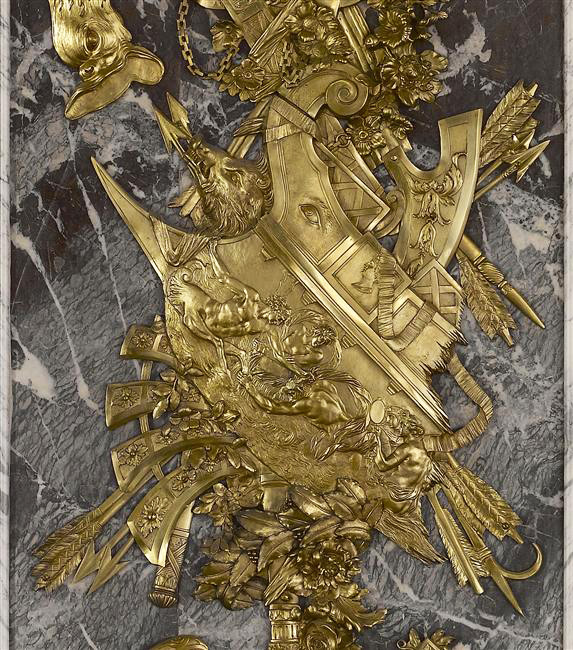

Gilt bronze was already used in Italy during the 17th century, but France, under Louis XIV's flamboyant reign, was the country that spread the use of gilt bronze all over Europe. During the Sun King's reign, luxury was omnipresent in architecture, paintings, gardens, and even kitchens, as it aimed to epitomize the richness and power brought to France by the absolute monarchy. André Charles Boulle, the King's personal cabinetmaker, who was described as “le plus habile ébéniste de Paris” (“the most skillful cabinetmaker in Paris”) by Colbert, brought bronze decoration to furniture. He was able to bring innovations to decorative arts thanks to his multiple talents as an illustrator, a bronze-maker, and a cabinetmaker. At first, gilt bronzes were mostly used in locksmithing (locks, door handles), and then they were used to protect the most fragile parts of the pieces of furniture – the angles and the feet – that they adorned with rich designs based on Antiquity, mythology, fauna and flora.

Under Louis XV, the use of gilt bronze continued to grow. Rococo-style furnishings were imaginative, with their fantasy, curved lines, asymmetry, and a sense of lightness and femininity. Gilt-bronze decorations were expertly crafted and represented rockeries, foliage, acanthus leaves, rushes, and shells. Louis XVI-style ornaments were much more minimalistic, inspired by Antiquity and nature, and many were especially designed for Marie-Antoinette. Tied ribbons, garlands, and draperies were frequent motifs. During the Second Empire and the Restauration, gilt bronze rose again. Napoleon III furnishings stand out for the abundance of richly crafted decorations, especially gilt bronze. An admirer of Marie-Antoinette, Empress Eugénie commissioned furnishings resembling the Louis XVI style.

Bronzes were seldom signed. A few important names from the Louis XVI, Empire, and Restauration periods are known, like Philippe and Jacques Caffiéri, Jean-Claude Duplessis, the Feuchère's, Jean-Joseph de Saint-Germain, François Rémond, and Pierre Gouthière.

Authenticating a gilt-bronze piece is always a delicate matter. There have been many replicas and frequent re-gilding from the 18th century to today. Unlike with other techniques, touch does not intervene much in identifying gilt bronzes. Experience and an eye for detail are more useful. Several factors can help; for example, French gilt bronzes from the 18th century are generally lighter and less thick than those from the 19th century.

Bibliography

VERLET Pierre, "Les Bronzes dorés français du XVIIIè siècle", Ed. Picard, 1987.