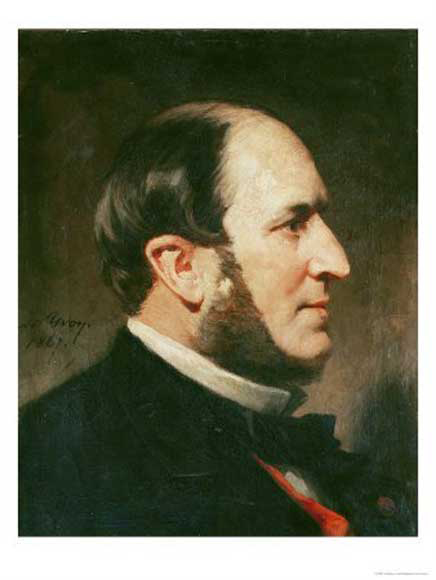

Baron Haussmann (1809 - 1891)

Download PDF Georges Eugène Haussmann (1809-1891), who became a Baron when elected senator in 1857, was a civic planner, well known for his massive renovation of Paris. As the Prefect of the Seine Department, he designed and led the transformation of Paris under the orders of Napoleon III, between 1853 and 1870.

In the mid-1800's, the center of Paris was dark, overcrowded, and unhealthy. While living in England, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte visited London, a city rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1666. He was very impressed with the spacious streets, modern city planning, and hygiene. Throughout the Second Empire, he wished to make Paris a city as modern and prestigious as London. According to architect Stephane Kirkland, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte was a visionary and an idealist who wished to rebuild Paris for the new industrial era. He would have played a central part in the creation of modern Paris, and immense project that he put Baron Haussmann in charge of.

Descended of a Protestant family from Alsace, Georges Eugène Haussmann had both paternal and maternal connections to the Revolution and Napoleon. His paternal grandfather had been a member of the legislative and conventional assemblies during the Revolution, while his maternal grandfather was a general in the time of Napoleon. Haussmann was born in Paris on March 27th, 1809, in a house that he would later demolish to build the small place between the Boulevard Haussmann and the Avenue de Friedland. He studied law in Paris.

A product of Napoleonic schools, Haussmann was no idealist and preferred concrete, rational, and feasible projects. His Memoirs portray him as a very serious, organized administrator. For example, he inventoried all of the furniture in each residence that he stayed at, and recorded a detailed itinerary of each of his journeys. The Memoirs also have accounts of the number of new gas lanterns compared to that of the oil lamps they were replacing, and the number of chestnut trees that were planted along boulevards. Haussmann's innate sense of discipline and his trust in the administration as the main vector for social change made him the Emperor's perfect partner in this project to renovate Paris.

Haussmann was not close to the Second Republic, proclaimed in 1848. Nonetheless, he supported the President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, and was therefore made Prefect of Bordeaux, and soon after that, of Paris. He would remain a supporter of Louis-Napoleon and the Bonaparte cause until his death on January 11th, 1891, in Paris.

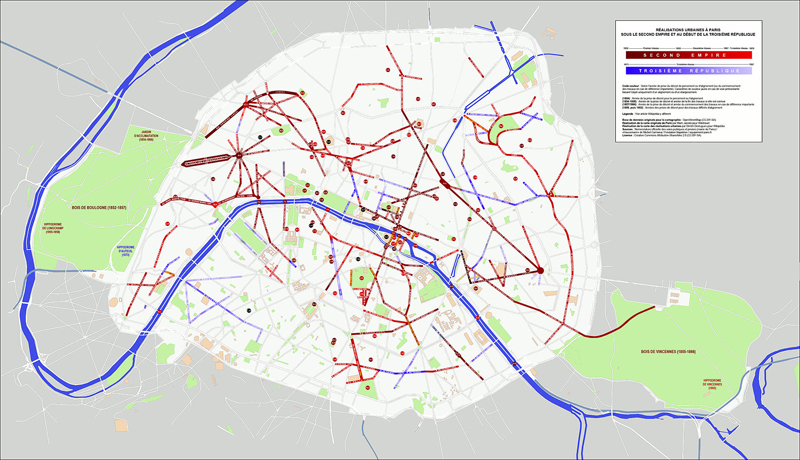

When he arrived in Paris as Prefect of the Seine, Haussmann met with Napoleon who showed him a map of Paris with the new streets that he wanted to build. The two men were about to take on the transformation of an essentially medieval city into a modern capital. This remains the largest urban renovation project in Western European History. This 19th-century project, led by Baron Haussmann and completed under the Third Republic, gave Paris its modern-day appearance. Other than the construction of the Eiffel Tower, the Sacré-Cœur, the skyscrapers at Montparnasse and La Défense, the Front-de-Seine, and the gentrification around the Bastille, Paris remains the city that Haussmann and Louis-Napoleon had imagined.

According to his Memoirs, Haussmann saw himself as the “devoted instrument”, “the principal worker on this colossal project.” He and Napoleon III met almost every day to discuss the work. Most of the time, it was up to Haussmann to accomplish the Emperor's large visions. The Prefect wielded enormous power, which led Adolphe Thiers to refer to him as the “vice-Emperor”.

Louis-Napoleon did not want to raise taxes to finance the project. Haussmann found a solution when he decided to unleash capitalism, stimulated and directed by government investment, and to levy duty on all products and materials that entered Paris. In this way, the city financed its own renovation, which was a very innovative strategy at the time.

The Emperor and the Prefect wished to transform their city socially, politically, and culturally. Haussmann's renovation was a central factor for the pacification of Paris. The reconstitution of urban space through the construction of extensive boulevards and the destruction of small, narrow, easily-barricaded streets protected Paris against the types of insurrections that it had so often been familiar with in the past, like the Fronde during the 17th century, or the 1848 Revolution, only 15 years earlier. Other than the Commune in 1871, Paris would never again be faced with such violent insurrections. In order to control such problems, Haussmann came up with the idea of making the city of Paris buy the Canal St. Martin, and then building a new boulevard (today the Boulevard Richard Lenoir) that would cross the canal and connect the Château d'Eau (today place de la République) and the place du Trône (today place de la Nation). This allowed the city to control “the habitual center of […] demonstrations” and to nullify the canal as a barrier. Louis-Napoleon agreed with this strategy.

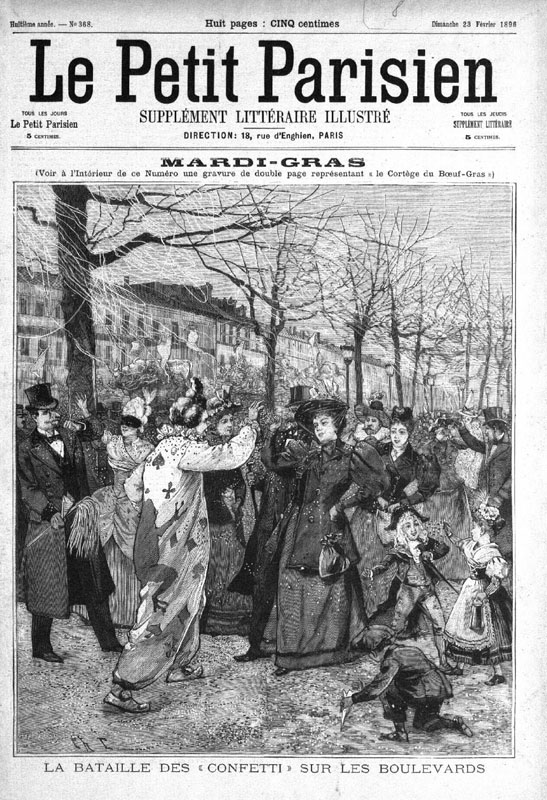

Haussmann and the Emperor's work didn't only lead to a strategic pacification of the city. It also created the Paris that we know today, a capital loved by its inhabitants and admired throughout the World. Parisian life was transformed by the "vie du Boulevard" (life of the Boulevard) and “l'esprit du boulevard”, which quickly became a characteristic aspect of Parisian life (see Illustration 6).

The Prefect created a new city plan (Illustration 4), with large avenues bordered by buildings that were more spacious and luxurious than the previous ones. He placed the big train stations around the city center. Long avenues were constructed, such as the avenue de l'Opéra and the avenue de la Grande Armée. Space was freed up around monuments to make them stand out, like the place de l'Opéra and the place de l'Etoile (today place Charles de Gaulle), where several avenues meet (Illustrations 3 and 5).

The Prefect expressed his passion for the rectilinear, monumentality, and aesthetic, classical urban planning, with his uniform buildings, places adorned with statues, and broad, linear avenues leading the eye to an isolated monument. He was influenced by his years living in Bordeaux, that had been modernized during the 17th century.

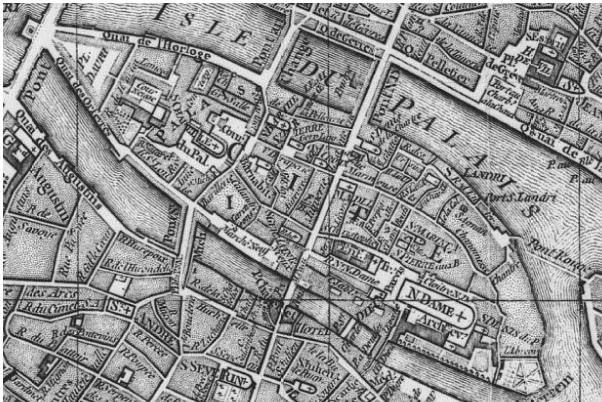

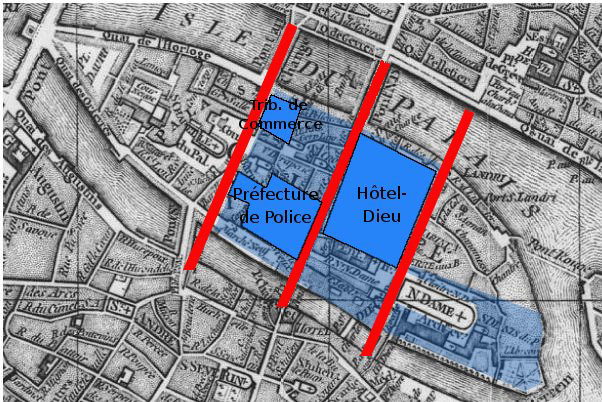

Under the Second Empire, the development of western Paris was reinforced by the construction of streets and parks such as the Bois de Boulogne and the Parc Monceau. Haussmann shifted the center of Paris westward toward the Opéra and the new boulevards. He transformed the Ile de la Cité and its surroundings to accentuate the magnificence of the city center's monuments and administrative buildings by isolating them. He created large spaces around monuments like the Hôtel de Ville, the Louvre, the Palais de Justice, and Notre-Dame. The parvis, the open area in front of Notre Dame (Illustration 7), was created at this time, spanning over 40 times more space than it had in the 12th century. According the David P. Jordan, French History scholar, the Ile de la Cité is the best example of the haussmanisation of Paris (Illustrations 8 and 9).

Haussmann, who was not very attached to the old Paris, wanted to bring safer and more sanitary living conditions to the city by creating not only large avenues but also parks and gardens, as well as a whole new sewage system to get rid of open sewers, and a water supply network. The Prefect and the Emperor also wanted to develop direct and practical transportation throughout the city. Although these transformations destroyed large parts of Medieval Paris, the city now had a better urban coherence, and larger, modern, open spaces.

The “Révolution Haussmannienne” that transformed Paris during the second half of the 19th century also modified the aesthetics of private buildings. Construction norms were created and enforced in order to ensure a sense of unity between the different buildings.

The “immeuble haussmannien” (Haussmann building) was born (Illustration 10). This type of building had to have a ground floor and an entresol (an intermediate floor); a third floor called the “noble floor”, with balconies; fourth and fifth floors in the same style but slightly less ornaments; a sixth floor with a continuous balcony and a 45-degree roof. The facades must be perfectly aligned, without any sunken or protruding elements.

Inside these buildings, the interior design is also carefully planned. The beautiful marble fireplaces in the styles of Louis XV, Louis XIV or Louis XVI are called “cheminées haussmanniennes”, or “Haussmann fireplaces”.

Bibliography

DANSETTE, Adrien, « L'Œuvre du Baron Haussmann à l'épreuve du temps », Annuaire-Bulletin de la Société de l'histoire de France, 1972, Editions de Boccard, Société de l'Histoire de France, p. 59-72.

JORDAN, David P., « Baron Haussmann and modern Paris », American Scholar, 1992, Vol. 61, p. 99-107.

MULLANEY, Marie M., « Review of Paris Reborn : Napoléon III, Baron Haussmann, and the Quest to Build a Modern City »,Library Journal, 2013, January 3rd, Vol. 138, Issue 4, p. 81.

Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, Georges Eugène Haussmann, Baron, Issue 4, 2016