Firebacks

Download PDFThe fireplace fireback, also known simply as "fireback" and often called "cast-iron fireback", is an object usually made of cast iron that is placed at the back of the hearth, in the fireplace. It is a fireplace accessory. It is pressed against the back wall in order to send back the heat from the firebox towards the room, and to keep the heat from being trapped in the wall.

Firebacks are usually made out of cast iron, which explains why they are often found in regions that are geologically rich in iron and forges (like Normandy, Lorraine, Champagne…). In certain regions, they are made out of granite (Brittany) or terracotta (Auvergne). They come in different shapes and sizes: square, rectangular, semi-circular, octagonal, trapezoidal…

To make a fireback, a sculptor first makes a wooden model, which is strongly pressed against wet sand to make an imprint; finally, the cast iron is poured into the imprint.

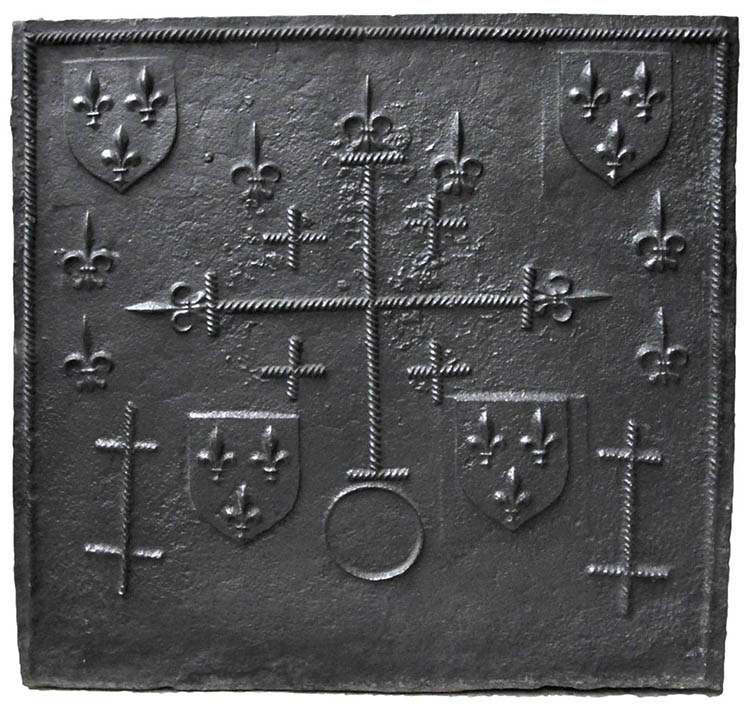

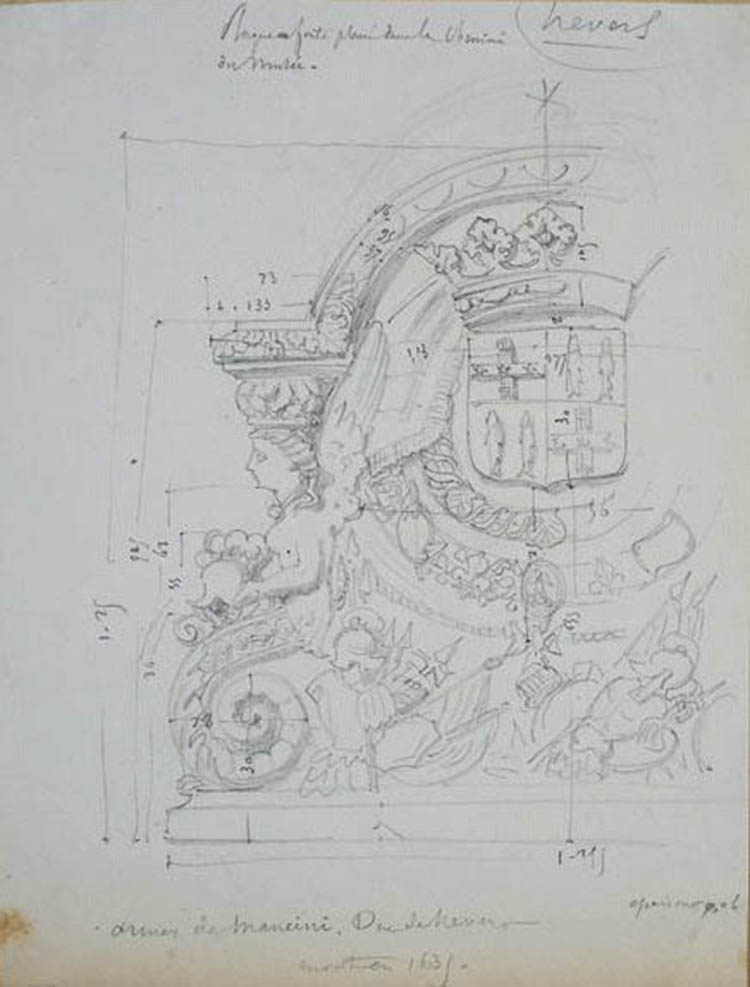

Firebacks were made in China as early as the 5th century, but it wasn't until the Renaissance and the middle of the 15th century that they arrived in Europe. They become more popular during the following century. The oldest fireback we know of, from 1431, is kept at the Lorraine Museum of Nancy. It is decorated with the coat of arms of King René of Anjou, a Jerusalem cross with four identical little crosses next to two Lorraine crosses on a background of fleurs de lys, the French royal flower.

Firebacks are decorated with more or less elaborate low-reliefs, usually the coat of arms belonging to the owner of the residence. According to Michel Pastoureau's forward to Philippe Palasi's work Plaques de cheminées héraldiques (Heraldic Fireplace Firebacks), this object is a very symbolic "mise en abyme":

« le château ou le manoir est le cœur du domaine ; la grande salle, le cœur de l'habitation ; la plaque à feu, le cœur de la cheminée ; et les armoiries, le centre même de la plaque ! » (the castle or mansion is the heart of the estate; the Grand Hall, the heart of the residence; the fireback, the heart of the fireplace; and the coat of arms, the center of the fireback!") (p.7).

Heraldic motifs are the most common decoration found on firebacks, as Philippe Palasi's in-depth study proves in his book Plaques de cheminées héraldiques (Heraldic Fireplace Firebacks, 2014). This study shows that some heralded firebacks were made for a specific client and, several years later, taken out for other buyers, meaning the arms were not always linked to a family, and could simply be a decorative design (possibly connecting the owner to an important local family). For the clients, adorning one's home with the arms of another does not seem to have been a problem. What about the one who commissioned the fireback, the wooden model? We know that certain great families kept the sculpted wooden model: in order to avoid copies, the original model was retained.

Looking to satisfy the clients' demands and to limit production costs, sculptors also made fireback models called "passe-partout" (master key). These have a design with an empty space in the center that the client would complete with his own arms (or leave empty if he wished). The commissioners did not seem to be attached to a specific decoration, as the personalization of the empty spaces allowed them to individualize their firebox.

The most commonly printed models are those with the royal coat of arms; these show the subjects' devotion to the King, as well as the trivialization of certain models.

However, some firebacks are decorated with different motifs: mythological or allegorical scenes, military scenes, human or animal figures. Surrounding the central design, there is often a secondary one. These compositions first appear during the Renaissance, but the golden age of fireplace firebacks has to be the 18th century, when the compositions resembled master paintings or engravings that were widely known by artisans.

Unfortunately, firebacks are never signed and it is therefore difficult to attribute or date them. Thanks to the most common design, the coats of arms, it is possible to partially date, localize, and attribute firebacks. Studying them also leads to distinguishing between the original firebacks and the copies, forgeries, and overmoldings that were made in later years. In fact, firebacks attained a certain commercial value during in the 1800's, and ancient molds were used to reissue firebacks (which is still done today).

Even though it is sometimes possible to date a fireback, the localization is not as easy, because firebacks have often been moved around, as their weight was never an issue. Firebacks often had to be shared as they became the sole representation of the family's coat of arms for its heirs. Other firebacks were simply removed from ruined or abandoned homes to adorn a new one…

Even though firebacks are subject to a sort of craze during the 19th century, it mustn't be forgotten that during the French Revolution, from 1793 to 1798, a very high number of firebacks were destroyed and melted. A decree, the décret du 18 vendémiaire de l'an II (October 9th, 1793), ordered their destruction. At the time, possessing a fireback adorned with royal attributes was enough to make the owner suspicious. He could then be sent to prison, or even sometimes to the guillotine. Some were simply turned around in the firebox, which saved them.

Today, we still have some quite exceptional, well-preserved firebacks from the 18th century, as well as some beautiful reissues from the 19th and 20th centuries (there have not been many original firebacks made since the Second Empire).

The Art Nouveau and Art Deco periods proved to be successful for highly technical ironwork with great artists such as Edgar Brandt (1880-1960) and Raymond Subes (1891-1970). A new production of fireplace firebacks began. However, after the Second World War, along with the generalization of modern heating methods, fireback production strongly decreased.

Bibliography

Henri CARPENTIER, Plaques de cheminées (Fireplace Firebacks), Paris, 1967.

Armelle MALVOISIN, « Cheminées : des plaques d'époque » (Fireplaces: antique firebacks), L'Oeil, Mars 2010, p.110-111.

Philippe PALASI, Plaques de cheminées héraldiques (Heraldic Fireplace Firebacks), Paris, Gourcuff-Gradenigo, 2014.